Mid-Back Tension Between the Shoulder Blades: Why It’s Not Just Tight Muscles

- 2 hours ago

- 5 min read

By Gavin Buehler

One of the most common complaints I hear is tension between the shoulder blades.

Given the daily postural habits we’ve adopted over the past few decades, this makes sense. We spend hours with a collapsed core, arms forward, shoulders rounded, and our head straining to stay upright. Whether sitting at a desk staring at a screen, looking down at a phone, or driving, we spend far more time in this position than we realize.

Many people try to offset their sedentary workday with exercise. Unfortunately, some of those activities — cycling, certain gym routines, even well-intentioned strength work — can reinforce the same forward-collapsed pattern.

It’s a rough battle.

Stating the Obvious

When you break down the shape of a rolled-forward posture, it’s easy to see why the mid-back feels tight.

From a vertical perspective, the erector spinae muscles along the spine are held in a prolonged stretched position, with the apex of the curve often sitting in the mid-back. They’re not just stretched — they’re straining for leverage to help hold up a head that’s drifting forward.

Add to that the position of the arms. With the shoulders rounded forward, the shoulder blades separate and glide around the ribcage. This places continuous tension through the rhomboids and mid-trapezius muscles attaching along the inner borders of the shoulder blades.

It feels tight because it is under constant load from all angles.

The Logical (But Incomplete) Solution

The common recommendation is straightforward:

Strengthen the stretched mid-back muscles

Stretch the shortened chest muscles

This approach is often described as correcting “upper crossed syndrome.”

In theory, it makes sense. In practice — after 20 years of strength coaching — I can tell you it’s rarely the full answer.

Muscles that are shortened from prolonged posture are usually weak as well. They need circulation, coordinated strengthening, and gentle lengthening — not just stretching alone.

While this model identifies observable patterns, it does not fully explain why those patterns develop or persist.

We’re missing the bigger picture.

Finding the Root Cause

We’ve compartmentalized the body into a stack of isolated parts, which it is not. It behaves more like a tensegrity structure — a system held together by balanced tension. (Read this post and its follow-up for a better understanding.)

Think of those old rubber-band push puppet toys. They stand upright because of constant resting tension. Press the button, and the whole structure collapses.

We’re similar — except when tension drops somewhere, we don’t fall over. We compensate.

And when we compensate, we’re no longer optimally stacked. The areas absorbing extra stress begin to “talk.” That mid-back tension? It may just be the loudest voice in the room, but not the root problem.

The Core Dysfunction

In both manual therapy and strength coaching, I consistently find core dysfunction to be a major driver of secondary complaints — including mid-back tension.

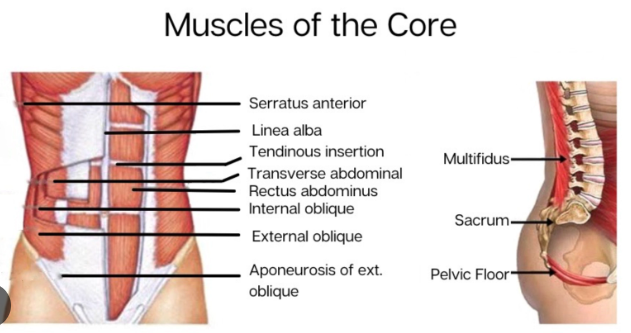

The “core” is often oversimplified, and fair enough because it is an intricate system, but it’s responsible for regulating resting tension throughout the body.

Virtually everything connects through the core. Structurally, this region dictates your baseline supportive tension.

And that tension is constantly influenced by sensory feedback from the environment we are in — What we feel through our hands, feet, skin, take in with our vision, taste, smell and emotions, can affect our body’s perception of how much resting tone we might require for any given situation.

The Sensory Feedback Loop

Let’s return to mid-back tension. Our body has adopted this position because of its environmental inputs.

Yes, ergonomics matter. Adjusting desk height and monitor position can help, but more often than not, you will find yourself slouched despite these changes.

In this example the biggest factor comes from where your body is perceiving the most support.

There’s a good chance you sit for at least 12 out of 24 hours each day — work, commuting, meals, relaxing. That’s 50% of your day receiving continuous feedback from a sturdy supportive surface under your pelvis.

Occasionally, that’s not a problem and likely needed from time to time.

Repeated daily, it changes your resting tension patterns.

Linking It Back to the Core

If there’s always solid support under you, the muscles responsible for providing integrity in that region begin to downregulate.

The message becomes: “We don’t need to work so hard here.”

Over time, they reduce their natural supportive tension.

Think of a cast on a broken arm — muscles atrophy from lack of use. Sitting isn’t that extreme, but the principle is similar.

In this case, we’re talking about the pelvic floor — a crucial component of sealing the “core canister” and regulating internal pressure.

When that tension decreases, slack enters the system.

And when slack enters the system, collapse follows.

Sitting day in and day out for extended periods of time depresses our push puppet button.

You can verify this simply by sitting or standing upright. Your core will automatically brace gently. Now completely relax your core.

What happens?

You slump.

Your tight pecs didn’t put you there.

Your lack of core support did.

An Alternative Solution

Instead of focusing only on the observable patterns and stretching the chest and strengthening the mid-back, consider restoring core integrity — for this example, especially pelvic floor engagement.

Reconnecting with this region and reducing total sitting time may have a far greater impact on postural tension.

General recommendations for deep core work often include the McGill Big 3:

These are excellent exercises. However, many people still struggle to effectively integrate the pelvic floor within them.

For that reason, I often recommend the Founder Pose as a catch all comprehensive way to reconnect the entire core system.

Keep in mind:

These exercises should all be tailored to specific individual needs.

An exercise is only as good as its execution. If any of the above-mentioned movements feel easy, I guarantee there is an error in your execution. I highly recommend seeking a professional who can deconstruct your case and provide you with the direction needed.

Bonus:

Exercise snacks can be a good remedy for sitting all day long. Not only will they offer the opportunity for your core to recalibrate, but a 2024 study showed that performing just 10 bodyweight squats every 45-60 minutes throughout a workday was more effective for blood sugar regulation than the well known and highly effective 30-minute walk. Maybe worth a gander.

Closing Perspective

For individuals who both sit extensively and train intensely, mid-back discomfort is common.

But in many cases, the symptomatic region is not the dysfunctional region.

When evaluating persistent tension anywhere in the body, the more productive question may be:

Is where I’m feeling the tension the problem — or is it compensating for altered central support?

Addressing the center often quiets the periphery.

Did you like this article and find it helpful? Please share it. Thank you!

As always, these articles and videos are for entertainment and educational purposes only. Please consult a health professional before attempting new exercises or protocols, as the following suggestions may or may not be appropriate for you.

Comments